Like many of you, I bought the six-year old in my life a giant Squishmallow plush toy last Christmas. It was the one thing she really wanted, and for weeks I was trying to find one that wasn’t hundreds of dollars. Why would anyone pay so much for these things, I wondered, and how do they make them feel so gross? In the end, I found a deal at Costco, and everyone was happy.

Yesterday our dog chewed it up.

I was sick, flat on my back, when it happened, and the kids were admirably playing by themselves while I slept, but that meant the puppy was unattended.

Was he mad that I’d thrown out the tattered remains of his dog bed earlier that day? He’d spotted me carrying it through the house. He was on the other side of the gate when I stuffed it in the bin.

My oldest daughter is convinced he was mad.

But why didn’t he destroy something of mine? I asked.

I was thinking the same thing, she said.

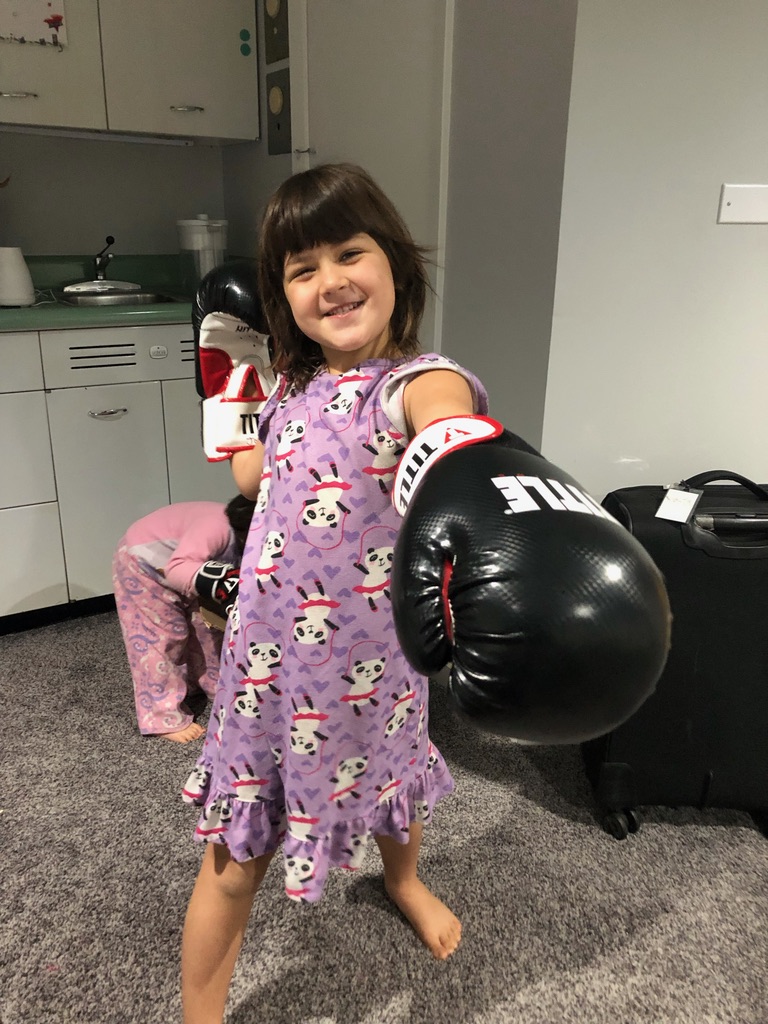

My nap ended abruptly when the Squishmallow’s owner came into the room, shouting and sobbing inconsolably. She had found her friend murdered and disemboweled on the floor of her room, murdered by another friend. I felt terrible for her and angry at the dog. I hauled him upstairs and put his face in it. I called him a bad dog, hoping that even if it was poor dog ownership, my daughter might feel my desire to stick up for her feelings.

Is there any chance the dog might somehow be able to link my displeasure with an act he’d committed in the distant past of five minutes ago? And that he might thereby be dissuaded from further destroying our shit? In truth, I wasn’t that angry in this instance, but sometimes I am. Angry at my lack of control. Puppies. Children. Myself.

How strange it is that we assume we can control our experience when we can’t even control our thoughts? Thoughts just arise, spontaneously, seemingly out of the ether, and if we can’t even control our own thoughts, which are precursors to our actions, how can we hope to control ourselves, let alone others? Throw in some additional randomness unrelated to the actions of sentient beings, like the car that won’t start or the roof leaking during a storm, and it’s pretty clear how much is out of our hands.

I’m not arguing that we should yield to chaos, but once we’ve embarked on a plan of action to improve an aspect of our lives or the world we live in, wouldn’t it be better if we could avoid feeding the self-referential thought loops about how we should have done this or that better or how we need to do those things better in the future?

Meditation can help with this, and not just in the way that learning to concentrate allows us to be selective about which thoughts we attend to, or even in the sense that we can learn to witness our thoughts with detachment so they feel less authoritative, but in the sense that it can help us recognize that we don’t exist in the way we tend to think we exist, that there is no self, no inner “me,” who needs to be promoted, berated, or defended.

After I put the dog outside, I got the shop vac from the garage and asked the girls if they wanted to help. It took only a moment for them to realize it would be kind of fun to play in the fluff.

After all, the Squishmallow wasn’t new anymore, and the puppy has destroyed so many of our things.

Besides, kids are good at letting things like this go. Better than us usually. They haven’t yet formed a rigid sense of themselves so there is nothing really for them to promote, berate, or defend.

In other words, there nothing for them to transcend, and in truth, there is nothing for us to transcend either because that inner me does not exist and has never existed, it just usually takes some looking for us to recognize it.

If you’re interested in learning how to look, you might want to check out Waking Up, the meditation app created by Sam Harris. In it you can find an ever-growing array of practices and information that can help with everything from learning to meditate to flourishing in daily life to dropping back into nondual realization (I should say here that I have no affiliation with Waking Up except as a subscriber).

And of course, I teach towards all of this in my yoga classes. You can find the in person and virtual schedules here.

Thanks for stopping by. If you want to get the posts by email, subscribe here. 👇

May all sentient (and squishy) beings happy and free.