What if this were the last thing you ever read in your life? Imagine for a moment that it might be. How would that change your experience?

As we go about our days, we tend to assume that we will continue to do the things we do again and again, but we don’t have to reflect for long to realize that at some point we will do each thing for the last time, and we never know when that will be.

This may sound like a gloomy thought, and if you were to dwell on it, it certainly could start to feel that way, but what if you could harness this knowledge to shift your perspective from one of reluctance or dread to one of eager engagement?

I’ll explain by way of example.

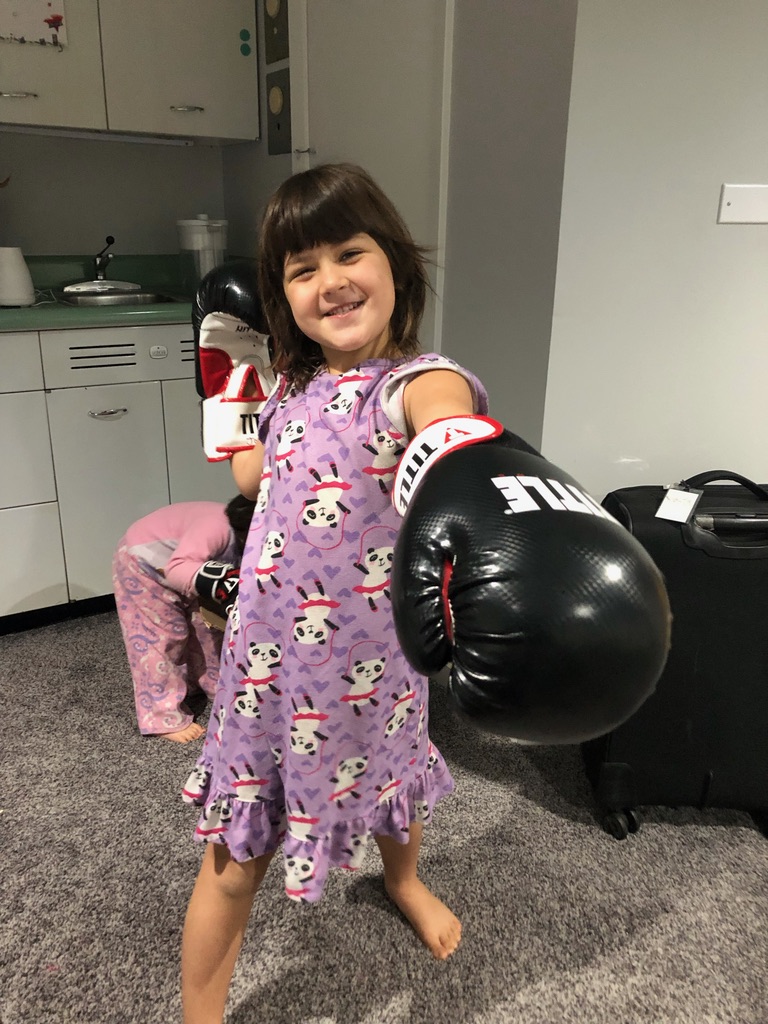

In my house, bedtime is often chaotic. Lots of shouting, crying, and wild behavior, and there are times when every step in the process can start to feel like an obstacle. Getting kids into pajamas, brushing teeth, reading book after book after book… Sometimes it goes smoothly (if not wonderfully), but often enough, it feels like a battle.

Yet if I can just take a moment in the midst of it and remind myself that THIS could be the last time I will ever brush my youngest daughter’s teeth, or help someone into a onesie, or read a beloved picture book, it can change my whole perspective on the situation, reminding me to see it as an opportunity to connect with someone I love and savour a fleeting aspect of one of the most important relationships in my life.

This reframing technique, which the philosopher William B. Irvine calls The Last Time Meditation, is taken from the Roman Stoics who developed tools like this to help them attenuate negative emotions, and I’ve found that it can be applied in a variety of situations to quickly shift my view.

Sometimes when I don’t feel up to teaching, for example, I briefly imagine what it would be like if this were the last yoga class I’d ever get to teach. Or when I don’t want to cook dinner, I imagine that this is the last meal I’ll ever get to prepare for my family. Even while writing this post, I asked myself what it would be like if this were the last thing I’d ever get to write.

Again, the point is not to dwell on the idea that all things eventually come to an end but to use–in the span of a few seconds–the fact of impermanence to help us rediscover a felt sense of what is precious about our chosen circumstances.

This is usually not necessary when things or relationships are new, of course, but as we all know, that luster wears off with disconcerting speed. This process, known as “hedonic adaptation,” and the way new desires rise up to take the place of desires fulfilled, was seen as a major obstacle to the tranquility sought by the Stoics.

In a traditional yogic framework, Patanjali, too, advocated pushing back against this human tendency. In his Yoga Sutras, the sage lists santosha, or feeling content with what one already has, as one of the five niyamas, or observances, that form the stable foundation for yoga practice.

“Without contentment,” writes Pandit Rajmani Tigunait, “we will never be able to slow the ever-spinning wheel of karma samskara chakra, the inexorable process by which mental impressions motivate us to engage in actions that, in turn, further strengthen the mental impressions.” (Tigunait, The Practice of the Yoga Sutra, p.172).

Put another way, each time we enact the cycle of desiring, acquiring, and then desiring something new, we reinforce the tendency to stay locked in a process where the baseline is constant seeking born of dissatisfaction with our current situation. What we want is always out there in some future that never arrives.

Unfortunately, most of the traditional yogic discourse I’ve encountered doesn’t suggest practical ways to directly access contentment. It’s often treated as if explaining its importance should be enough to allow us to drop this human hankering after something more than what we have. Granted, more contentment will likely arise with prolonged practice of yoga, but by contrast, The Last Time Meditation gives us a chance to quickly reframe things whenever we get caught in the cycles of desire or aversion that carry us away from what we really value.

The Last Time Meditation is certainly more of a top down, metacognitive (using thinking to affect thinking) approach than the bottom up (working with the breath and the body) or thought-transcending approaches familiar to many yogis, and because of that, it might sound like weak sauce, but if you mistrust it on that level, consider this:

In the year 65, Roman Emperor Nero was advised by his counselors that his tutor, the Stoic philosopher Seneca, had conspired against him and ordered Seneca to commit suicide.

Here’s how that went down:

“When the friends who were present at his execution wept over his fate, Seneca chastised them. What, he asked, had become of their Stoicism? he then embraced his wife. The arteries in his arms were slit, but because of age and infirmity, he bled slowly, so the arteries of his legs and knees were also severed. Still he did not die. He asked a friend to bring poison, which he drank but without fatal consequences. he was then carried into a bath, the steam of which suffocated him.”

William B. Irvine, A Guide to the Good life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy, p. 47

The way I see it, if Seneca could use his Stoicism to not only endure such a fate but upbraid his friends for failing to keep a stiff upper lip in the process, it seems like giving The Last Time Meditation a try might be worth the small amount of effort it takes. It probably won’t work in all circumstances, and it may not work for you at all, but if it does, it might just help you get everyone tucked into bed tonight in one piece.

🙌 ❤️ 🕉

If you’re looking for more useful methods improve your day-to-day experience, come practice with me. Here is my live class schedule (both in person and virtual) and here is my YouTube channel (for pre-recorded content). You can also sign up to get these posts by email so you won’t miss any of the other low-hanging fruit I like to dangle about. 👇

Thanks for stopping by, and thanks, too, to William B. Irvine for his excellent intro to Stoicism, A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy (Oxford University Press, 2009). Also, if you’re looking for a fresh commentary to the Sadhana Pada, portion on practice, of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra, Check out The Practice of the Yoga Sutra, by Pandit Rajmani Tigunait (Himalayan Institute, 2017).