It happens fast. One moment, the tiny plastic skydiver is parachuting peacefully down from the second floor balcony, the next it’s getting shoved up someone’s nose. A retaliatory eye gouge that would horrify a Muay Thai pit fighter ensues, and suddenly, sobbing children are running out the front door in their underwear in five-degree-below-zero weather. And you? You’re standing on the porch, apoplectically threatening to cancel Christmas, which is still ten months away.

It’s no secret that kids are, shall we say, emotionally labile, and they are masters at infecting us with their insanity in ways that impair our ability to manifest our best selves. And in these pandemic conditions, with parents working from home (or not working from home) and kids doing school from home (or not doing school from home), we are not only trying to navigate the challenges of our occupations without the communities, equipment, peer groups, release valves, and support mechanisms on which we formerly depended, we’ve been thrust into a bizarro universe where we have to do things like try to convince a Farm and Fleet manager in Chippewa Falls that she should order an extra five-hundred units of dog chow while picking lightbulb shards out of a hyperventilating toddler’s foot.

By the time you get to your last Zoom meeting of the day, you may be in a state where you think you can cajole the head of the rail workers union into exempting you from a COVID surcharge that will force the closure of your Whitehall distribution center by playing “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” and asking him where his belly button is. Yes, he may be a “big boy.” But do not ask him, “who’s a big boy?” You also must not remind him that “sharing is caring,” try to send him to time out, or withhold dessert if he does not comply.

Even if you don’t have kids at home, you’ve surely gotten mixed up in similar fashion. The way we are cooped up and on top of each other (or isolated) all the time, it should be no surprise if you’ve inexplicably gone off on your partner or roomate or pet or fern or whatever. We’re still pretty stressed out, even if we’re sort used it by now.

If you’re reading this, you’ve probably already had some first hand experience with the ways that yoga can help you cope with stress, so I’m not going to travel down the rabbit hole of discussing the autonomic nervous system, increasing vagal tone, or speculate about the length of your telomeres.

What I am going to do is offer up a few tools from the Tantric tradition (the branch of yoga that teaches us to see the sacred in the mundane) that may help you train up your ability to shift gears quickly when the situation demands and take on challenges with your higher cognitive faculties intact. My intention is that you’ll be able to add these techniques into your existing asana practice, yoga teaching, or other regimes of training.

Here goes.

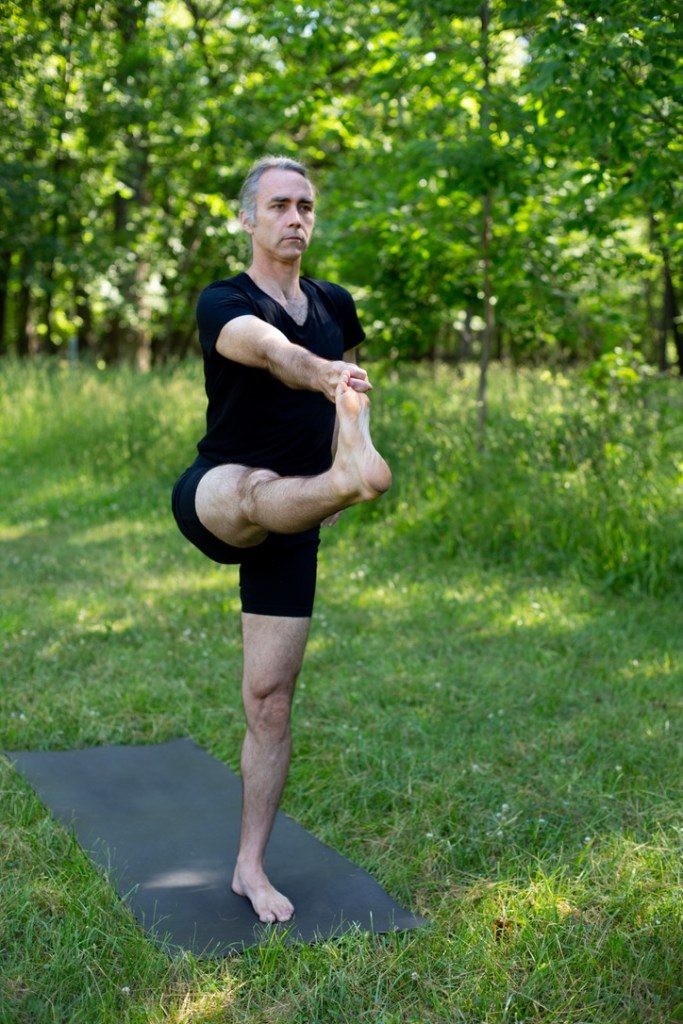

- Kaya Sthairyam – kaya (body) + sthairyam (steadiness) Literally holding the body still. This is frequently taught as a seated practice, but the principles can be incorporated into even a vigorous movement practice. After a challenging posture, sequence, or set, put yourself into a hub pose and try to remain perfectly still. A hub pose is any symmetrical pose where you don’t have to use much concentration to maintain the asana. In studio classes, we are often encouraged to take child’s pose when the breath becomes ragged or we need a break, but the emphasis here is not merely on recovery. Instead, we are cultivating the ability to notice what is happening with the breath, the heartbeat, the energetic quality of the body, and the thoughts in the mind while in a state of arousal. If we can start to notice when these markers appear and practice not reacting to them (even at the level of fidgeting) we have a better chance when we are off the mat of stopping ourselves before we tip over into hyperarousal–and lose our minds or collapse into catatonic dissociation 😵. This practice can also help to cultivate pratyahara (turning the attention inward). As Swami Satyananda Saraswati points out in A Systematic Course in the Ancient Tantric Techniques of Yoga and Kriya, “After practising kaya sthairyam intensely for even a few minutes, you will find that the awareness spontaneously directs itself inwards.”1 Child’s pose is one example of a hub pose. Some others are tadasana (mountain pose), savasana (corpse pose), the passive variation of nakrasana (crocodile pose), and for practitioners who are very comfortable in it, adho mukha svanasana (downward-facing dog).

- Kumbhaka – Breath Retention. According to the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, “When prana moves, chitta (the mental force) moves. When prana is without movement, chitta is without movement. By this (steadiness of prana) the yogi attains steadiness and should thus restrain the vayu (air).”2 Stopping the breath creates gaps in the mind, which can halt the inertia that carries thoughts and actions through their habitual patterns. By weaving these retentions into a physical practice, we can learn how to suspend our momentum and then restart it again on a clearer footing. Breath retentions can be of two types, antar kumbhaka (internal breath retentions) and bahir kumbhaka (external breath retentions). They are often practiced with the use of bandhas (energetic locks) and should only be performed once the breath is calm.

- Pranayama – prana (inner breath) + ayama (to lengthen). Pranayama is one of the most effective and direct ways to explore and work with the energies of the body. It is well supported by yogic experience and a growing body of scientific literature3 that pranayama practices, when performed correctly, have salutary effects on the body and lead to more balanced, calm, and energized states of mind. Pranayama is most commonly thought of as a seated practice to be used after asana, before meditation, or on its own, but if we are willing to think of pranayama more liberally as extending the breath, we can also bring it into our asana practice. During breath-connected movements, see if you can make the inhalation or exhalation last longer than each movement. This can help you avoid the tendency to unconsciously accelerate in sequences like sun salutations or other repeated flows where you have to exert some effort. This practice of extending the breath can further be supported by thinking of each movement or static pose as a support for your breathing practice (rather than the other way around) and by noticing the brief pauses between inhalation and exhalation. If we can become adept at attending to the breath in this way during practice, it can trigger us to start using the breath to focus the mind and keep our energies within manageable bounds when stress arises in other contexts.

To learn to work safely and effectively with any of these practices, it’s best to find a teacher who can show you the way. Once you’ve had some competent instruction, you’ll have to experiment to find out exactly how they affect you and how to best employ them to receive your desired results.

I’d also like to add a caveat here: while I have experienced the described benefits of these subtle-body practices, I think it is easy to get lost in the weeds of trying manipulate your energies to fine tune your experience. Indeed, if you look through the classical texts like those mentioned above, you’ll discover that many of the practices can get pretty complicated and may start to feel esoteric or overreaching in their claims. Moreover, many of the recommendations for the application of some of these practices may not fit into your life in a way that will allow you to fulfill your worldly responsibilities.

For me, the greatest benefit of incorporating these techniques and their underlying principles into my practice has been the way they turn my attention inward, improve my tolerance for wide array of internal experiences, and help me work skillfully with different self states both on and off the mat. What’s more, engaging my interior landscape as a play of energies rather than as a narrative about what I think should be happening gives me a way to handle stressful situations that’s free of the baggage of my beliefs and theories, which gives me a better chance to avoid throwing fuel on the fire and reinforcing patterns of reactivity in me and my kids. Having trained in this way, I have at least a better chance of responding to changing circumstances in creative and intentional ways.

I hope you find some of these strategies useful. If you want to explore some of them with me, please join me for a class. I’m currently teaching a live virtual vinyasa class on Thursdays at 8 am central through Ahimsa Yoga Studios. You can always find an updated class schedule on my classes page, along with links to a few of my recorded classes on YouTube. From there you should be able to find more of my videos.

Thanks for stopping by. If you want to get the posts by email in order to stay up with new classes and other offerings, type your address in the box below👇 and click the blue button.

1. Swami Satyananda Saraswati, A Systematic Course in the Ancient Tantric Techniques of Yoga and Kriya; p. 206; Yoga Publications Trust; Munger, Bihar, India; 2013

2. Swami Muktibodhanandanda; Hatha Yoga Pradipika; p. 150; Yoga Publications Trust; Munger, Bihar, India; 2014

3. PubMed.gov https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32669763/

One thought on “Tantric Tools for Autoregulation”